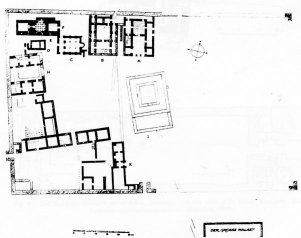

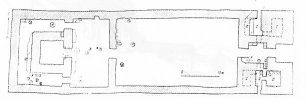

In the three centres of the proto-Bulgarian empire there exist temple

buildings of a singular and uniform type whose origin cannot be traced

back either to ancient or to Slav prototypes. The Pliska temple, discovered

in 1939-1940, is described by Stancev [1] as the «foundations

of a large building, its planimetry consisting of two squares, one being

inserted concentrically within the other, and of a southern vestibule —

probably added a little later». The building «probably dates

back to the same period as the palace of the throne. The edifice was later

demolished and razed to the ground». The temple (figs. 1-2) is to

be attributed to the late 7th or early 8th cent., and after its destruction

it was replaced by the churches to the west of the "Small Palace" of Pliska.

This temple-church sequence that can only be shown stratigraphically at

Pliska is unequivocably evident at Preslav. Stancev writes [2]:

«To the south, in the neighbourhood of this square are to be found

the foundations of a building known for some good time but hitherto not

clearly explained. These foundations are devoid of supports for a roof.

On the same spot remains of a church are also extant. In the centre of

its naos there is a raised square built of stone in the middle of which

there rises a pier built of masonry. This fact is to be explained as follows:

here, too, at first, there was a building consisting of two squares one

inside the other, a structure already familiar to us owing to building

I in the centre of the palace quarter of Pliska. The building has here

been transformed into a church by adding an apse to the east of the outer

construction (a slightly elongated rectangle) as well as a number of buttresses

to the corners of the west wall... Without going into details we should

like merely to observe that we have good grounds for assuming that a Slav

or proto-Bulgarian pagan sanctuary existed here and was later transformed

into a Christian church. The same is also true of building I at Pliska

».

|

|

| Fig. 1 - The square temple of Pliska (building I), Northern Bulgaria. Beginning of the 8th cent. A.D. (Author's photo) | Fig. 2 - The square temple of Pliska (Building I). (From

STANCEV, Pliska and Prelsav: after Mavrodinov).

|

|

|

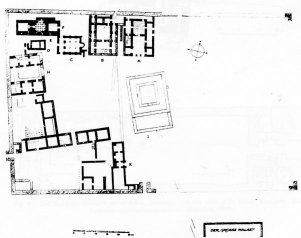

| Fig. 3 - The «Palace» of Madara, with overlying church. 8th cent. A.D. (From FEHER, Archeologia Hungarica, VII, 1931) | Fig. 4 - The square temple in the church of preslav,

Northern Bulgaria. 8th cent. A.D. (Author's photo).

|

As builders, the Slavs must indeed be ruled out insofar as the culture

of the centres of the proto-Bulgarian empire (and Pliska, Preslav and Madara

were the settlements immigrating Proto-Bulgarians preferred) was probably

shaped by the superior non-Slav stratum. It is Stancev himself who remarks

[6]:

«The foundations of Pliska and Preslav are the outcome of evolution

and reflect it», and he goes on to note: «These two strongholds

differ sharply from truly Slav cities in our country...». «The

material culture of the Proto-Bulgarians has late-Sarmatian, or more properly,

Sarmatian-Alan features... This culture or, as is more likely, that of

the tribal aristocracy, prevailing among the Proto-Bulgarians, was seriously

influenced by the culture of the Turkic peoples coming from the East, peoples

who either shunned the Proto-Bulgarians or gradually and imperceptibly

blended with them » [7].

|

|

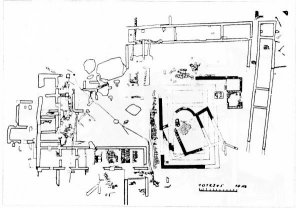

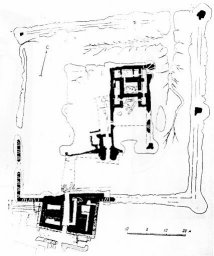

| Fig. 5 - Babiš-Mulla I, east of the Aral Sea. 4th-2nd cent. B.C. (From TOLSTOV, Po drevnim del'tam...). | Fig. 6 - The Buddhist Monastery of Ak-Bešim, Semirecye. 7th-8th cent. A.D. (From KYZLASOV, Trudy Kirgizskoj arheologo-ethnograficheskoj Ekspedicii, 1959). |

This hypothesis is borne out by the inscription Tangra on a marble column [8] from Madara, an inscription that in all likelihood indicates that this locality was consecrated to Tengri, the Turkic god of the sky. In actual fact, the column comes from an «elevated place», not from the square-shaped temple, and indeed, as far as I know, square-shaped temples dedicated to the god of the sky are unknown. In the Bulgarian language one generally dubs these structures as "pagan" and no more. It is likewise impossible to specify what divinity was worshipped in the square-shaped temples, for all the relevant clues — for example, statues, etc. — seem to be missing.

As regards the origin of the builders of these three temples, we must look for their prototypes in the Central-Asian area. In such an area, especially in the Parthian-Kushan region, quite a number of square-shaped temples with a surrounding corridor are to be found: there are also "imperial" sanctuaries in the full sense of the word like the one at Surkh Kotal — that is, the famous sanctuary of Kaniska in Afghanistan [9]. Constructions of this sort are also matched in the area of Parthian influence in the Near East — the square-shaped temple of Hatra [10] is an example of this. The relative prototypes could be looked for in eastern Aralia, for in that region the palace of Babiš-Mulla I, for example [11], dating from the 4th-2nd cent. B.C., adhers to the same building scheme: though here the corridor has been transformed by transverse walls into an entrance-passage giving access to the rooms (fig. 5). The temple that is supposed to have stood beside the palace has not yet, alas, been brought to light. As, however, the palace was continued in the residence of Halcajan in the early Kushan epoch [12], one feels entitled to suppose that the temple of Babiš-Mulla was homogeneous with the Kushan sanctuary of Surkh Kotal.

Surkh Kotal has been rightly interpreted by the archaeologist who excavated it [13] as «a fire sanctuary in honour of the ruling dynasty». May one assume that even among the Proto-Bulgarians fire temples existed as temples of the empire? This cannot be proven, since excavations have provided no evidence of those characteristic layers of whitish ash present in the Iranian fire temples.

There is, in truth, a further possibility that has not as yet been debated. The corridor serving for circumambulation around the square-shaped cella could have been used in the ritual practices of a religion that from the lst-2nd cent. A.D. had penetrated Central Asia reaching the northern part of Central Asia in the 7th cent. at the latest — that is, the area crossed by the Turks who adjoined the Proto-Bulgarians. The religion in question was Buddhism. In the Land of the Seven Rivers (Semirecye), inside a city extending over 25 hectares, the city of Ak-Bešim [14], a Buddhist monastery has been found (fig. 6) dating back to the age which saw the beginnings of the proto-Bulgarian temples of Pliska, Preslav and Madara. This construction is 76 m. long by 22 m. wide. The courtyard, 32 m. by 18 m. in size, divides the residential area from a temple measuring 23 m. by 18 m. The sacral building rests upon a plinth and consists of two quadrangular units one within the other and an atrium as well, just as at Pliska. The singular slabs of gilded bronze recovered from this monastery lead one to postulate a syncretistic form of Buddhism under Turkish influence. The Ak-Bešim temple is not an isolated phenomenon, although the other Buddhist sanctuaries of Kirghizia do not reveal a symmetrical plan of this kind.

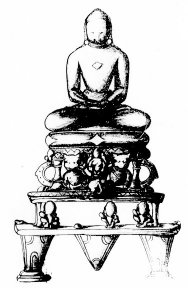

In this respect, a bronze image found in north-east Bulgaria in 1928

is, perhaps, important. It represents what is probably the figure of a

Jina and dates from the 8th-12th centuries. The place where the find occurred,

Kemala, is situated 30.5 km. from Razgrad in the museum of which the statue

is to be found. Unfortunately only a preliminary publication containing

drawings is in existence [15]. According to the information

given, the figure was removed from a depth of 70 cm. but not, alas, under

the supervision of specialists; it was later placed in the museum (figs.

7-10). The figure, about 13.5 cm. high, rests on a plinth consisting of

three steps. On the second of these there were four tiny human figurines

one of which is missing. The topmost level is embellished externally by

two decorations shaped like an arch, each of which is continued internally

by a column. Beside each there is a lion followed by a serpent. The two

serpents surround an elephant (?) upon which a female figure is recognizable.

On the chest of the figure of the Jina there is a rhomboidal mark (śrivatsa).

The ears have become transformed into dangling tresses. Unfortunately,

the figure is very worn so that an exact definition of the period it belongs

to is difficult. It could be assigned to the 8th-12th cent., and could

therefore have been imported in the proto-Bulgarian period.

|

|

| Figs. 7, 8. Image of a Jina.

From Kemala-Razgrad, |

North-east Bulgaria.

Razgrad Museum |

|

|

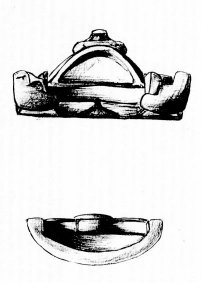

| Figs. 9, 10 - Side view and

plans of the Jina image in figs. 7, 8. |

Bearing in mind that the Jainas, as merchants, travelled widely, it could in this case amount to an isolated importation like the Buddha of Helgö [17] in Sweden. Be that as it may, the statuette tells us little about the temples of the Proto-Bulgarians, but like these temples it points to the East.

3. G. FEHER, «Les monuments de la culture protobulgare et leur relations hongroises », Archaeologia Hungarica, VII, 1931, fig. 27.

4. STANCEV, op. cit., p. 242, note 3.

8. I. VELKOV, «Madara», in BEŠEVLIEV, IRMSCHER, op. cit., pp. 265-271; see p. 268.

9. D. SCHLUMBERGER, Der hellenisierte Orient, Baden-Baden, 1969, fig. 26.

11. S.P. TOLSTOV, Po drevnim del'tam Oksa i Jaksarta, Moskva, 1962, drawing 89.

12. G.A. PUGACENKOVA, Halcajan, Taskent, 1966, fig. 23.

13. SCHLUMBERGER, op. cit., p. 63.

14. L.R. KYZLASOV, «Arheologiceskie issledovanija na gorodisce Ak-Bešim v 1953-1954 gg.», Trudy Kirgizskoj arheologo-etnograficeskoj Ekspedicii, Moskva, 1959, pp. 154-227.

15. Otcet VII na Razgradkomo arheologicesko drucestvo za 1930, pp. 8-11.

16. According to information in a letter by H. Plaeschke, Halle.

17. D. AHRENS, « Die Buddhastatuette von Helgö», Pantheon, XXII, 1964, pp. 50-52.